Suburban residence dating from around the 1940s, which has been added to and much altered over the years. During the time that the Naudes lived here, this was a fairly modest 3-bed-roomed home.

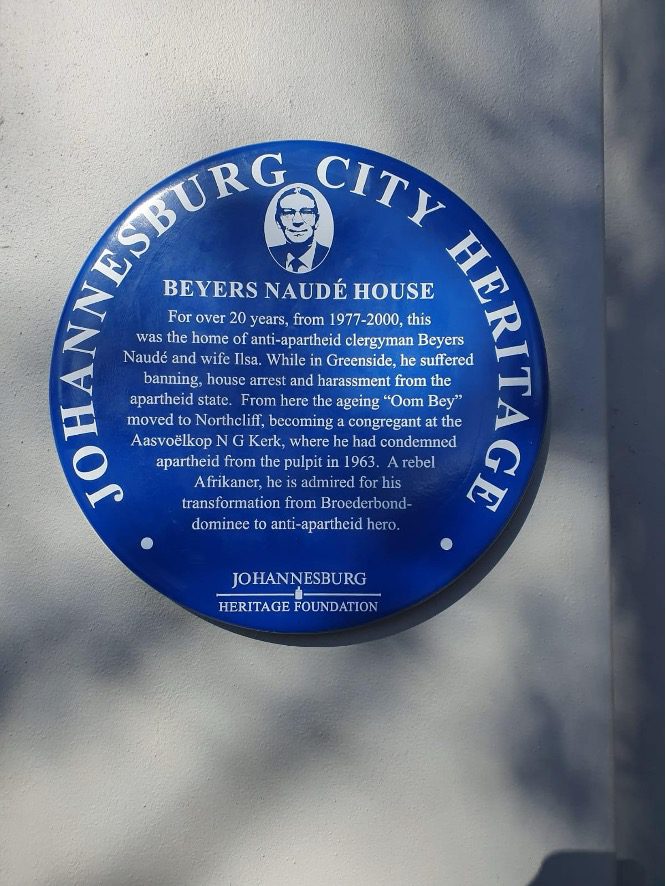

For a period of over 20 years, from June 1977 until around 2000, Beyers Naudé and wife Ilsa lived at the Greenside house at 26 Hoylake Road after moving there when their children had left the nest. Four months later Naudé was banned and placed under house arrest, and the Christian Institute was closed down. This was a period of intense anti-apartheid campaigning by Beyers both within church structures and the wider society.

Prior to moving to his home in Hoylake Road, Beyers Naudé and his family lived for many years in Greenhill Road, off Clovelly Road in Greenside.

During his time in Greenside, he suffered harassment from the apartheid government, but that did not stem his vigorous commitment to social change, and he used his time during house arrest to reflect on issues of faith and social justice. The time became meaningful for him as he met with a wide range of people in his intimacy of his study, particularly those from black communities, where they shared their vision of the future with him.

Beyers Naudé was born in Roodepoort, in the then Transvaal, on 10 May 1915. He was named after Christiaan Frederik Beyers, a Boer general who was close to his father, Jozua Naudé. Naudé was one of eight children and was born into a family committed to Afrikaner nationalism. His father was a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) and was a founding member of the Afrikaner Broederbond, a secret society aimed at promoting Afrikaner interests and white supremacy.

In 1921, the family moved to Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape. Here Naude matriculated at the Afrikaans Hoër Volkskool in 1931 before following in his father's footsteps by studying theology at the University of Stellenbosch. He also joined the Broederbond as its youngest member when he was only 25.

In 1940 he was appointed a ssistant-m inister at the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) in Wellington, Cape Town. In August of the same year he married Ilse Weder, the daughter of a Moravian missionary.

For the next twenty years Beyers Naudé ministered to various congregations across the country. He followed the political philosophy of the National Party, but the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 brought about a huge change of heart. He had already begun to question the morality of apartheid after witnessing the destruction of b lack family life under the migrant labour system.

1961 saw Naude beco me acting moderator of the Southern Transvaal DRC synod despite his outspoken opposition to apartheid. Later that year he was appointed moderator. He was the founder of the Christian Institute, a non-racial ecumenical organisation that challenged church establishment while providing humanitarian relief. Naudé was also the editor of the Christian Institute's publication Pro Veritate.

Naude was serving as Dominee (Minister) in the Aasvoëlkop congregation during this time and experienced intense inner conflict regarding the church's support of apartheid with his own Christian principles. This caused him to resign from the Broederbond after 22 years of membership. However, the real turning point came on a Sunday morning in September 1963. Already considered a traitor for quitting the Broederbond, he braved complete rejection by the Afrikaner community by condemning apartheid from the pulpit at the Asvoëlkop Church in Northcliff, resulting in his expulsion from the NG Kerk.

After completing his last sermon in which he placed “the authority of God before the authority of man”, he removed his robes and left his church. Naudé and his family were completely ostracized by their fellow Afrikaners. He told his wife, “Whatever happens, we will be together and God will be with us.” Naude was embraced by the b lack community and joined a Dutch Reformed congregation led by Reverend Sam Buti in Alexandra.

His induction as an elder of the Parkhurst DRC in March 1965 caused upheaval in the church community. While addressing youth, he was harassed and forced out of the DRC building in Belgravia. He continued in his position as Director of the Christian Institute, but in May 1965 had the unfortunate experience of the Security Police raiding the organisation's premises.

Naude was opposed to violence as a means of change and in 1972 he travelled to Europe where he delivered a sermon at Westminister Abbey, London. He became the first Afrikaans t heologian to be honoured in this way. He continued on to West Germany for talks with church leaders there. Towards the end of the year he was awarded an honorary doctorate in t heology by the Amsterdam's Free University for ‘exceptional merit for the development of theological science'.

The following year Naudé refused to give evidence to the Schlebusch Commission, a parliamentary Commission which had been established to investigate the Christian Institute, the University Christian Movement, the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) and the Institute of Race Relations.

Two years later in October 1975 he was fined R50 or one month’s imprisonment for refusing to testify before the Schlebusch Commission. Naudé was arrested on 28 October 1976 for refusing to pay the fine. After spending the night in jail the DRC minister, Dr Jan van Rooyen, paid the amount and he was released. In December 1975 Naudé was refused a passport to travel to London to address the Royal Institute of International Affairs, and his speech was presented in his absence.

1974 saw Naudé receive an honorary doctorate of Law from the University of Witwatersrand. He was also honoured with the Reinhold Niebuhr Award for ‘steadfast and self-sacrificing services in South Africa for justice and peace'. His passport, which had been confiscated, was returned so that he could travel and receive the award at a ceremony in Chicago, United States of America. On his return his passport was confiscated again.

Naudé and his Christian Institute were banned in October 1977. Despite continual persecution he established a ministry to council pastors. He was not allowed to leave his house, or speak to more than one person at a time. He continued to speak to other anti-apartheid activists like Archbishop Desmond Tutu on a one to- one basis.

Naudé was awarded a prize for reconciliation and development from the Swedish Free Church and an award from the Bruno Kreisky Foundation in recognition of his ‘untiring work in race relations'. By 1980 Naudé broke away from the DRC and was admitted to the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk (NGK) in Africa. His banning order was renewed for a further three years in 1980, but was eased. He was allowed to leave his home, but not the Johannesburg magisterial district. In June 1983 Dr Naudé was awarded an honorary d octorate from the University of Cape Town.

During his house arrest, it is believed that he used to repair the cars of ANC members in his driveway at the Greenside house. After seven years Naude's banning order was lifted in September 1984. He immediately threw himself back into the struggle against apartheid. He succeeded Archbishop Tutu as the Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches (SACC) in 1985. Two years later he formed part of the Afrikaner group that met with ANC representatives in Senegal.

While serving the SACC, Naude developed heart problems, he however postponed surgery because of his heavy commitments. By November 1986 he had no choice but to undergo surgery to correct two leaking valves. He was advised not to go back to work till February, however by early January he was back at his desk.

Much of Beyers’ work happened behind the scenes although he had had an uncompromising stance in his support for black rights. He supported the Kairos Document which challenged the churches, if they were serious about reconciliation, to reconsider their theology. Naude also added his voice to the call from leading churchmen, black organisations and trade unions for civi l disobedience and for economic sanctions against South Africa as a means of pressuri ng the government into ending apartheid.

His other work also included serving as a trustee on the board of several anti-apartheid organisations. He travelled widely although struggling to get access to a passport. Regardless, he made numerous guest appearances at government, church and political groups. He preached on a guest basis at churches all over the country, including his Alexandra church. In his later years he continued to make himself available to people and showed equal respect for the humble and the mighty. People continued to stream to him, and on a normal working day he would see more than 10 people.

After hearing President F W de Klerk 's speech in 1994, declaring a new South Africa, he said 'Gee, at last! What I had dreamt, hoped and worked for is becoming a reality.'

The demise of apartheid and the move to democracy around 1994 turned Naude from pariah in the eyes of the state, to becoming acknowledged as a national hero. On his 80th birthday, President Nelson Mandela called him a “living spring of hope for racial reconciliation”.

In June 1999, despite failing health, he opened the inauguration ceremony for President Thabo Mbeki. By the end of the same year he returned to his old congregation of Aasvoëlkop as a congregant.

On 19 January 2000, Beyers Naude sold his house to Jacomi du Preez and moved into a frail care facility at Elm Park Retirement Village in Northcliff, Aasvoëlkop , a suburb where ‘Oom Bey' had previously led a congregation and attended services.

Beyers Naude has been honoured by numerous honours and awards, including:

General Protection: Section 34 (1) Structures under the National Heritage Resources Act, 1999.

A culmination of research gathered over many years, the Online Johannesburg Heritage Register is being launched on Nelson Mandela Day 18 July 2025.

Among the many heritage sites featured is Chancellor House, the downtown offices of Mandela and Tambo Attorneys in the 1950s. After having been vacant and shuttered for more than a decade, this iconic building is being revived and brought to life once again as offices for the Community Development Department, which oversees the City’s Arts, Culture & Heritage Services.