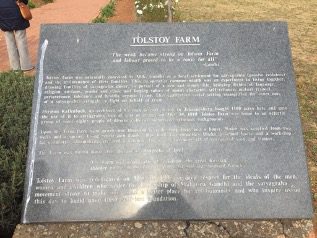

Within the broader site corresponding to the historic Tolstoy Farm, a commemorative area has been established close to the southern ridge. A landscaped Peace Garden includes flowers, plants, trees and a vegetable garden. A series of heritage plaques are displayed, as well as large busts of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. A plinth structure stands near the centre, with red stairs leading up to what used to be the entrance of a large farmhouse that no longer exists. Close to the plinth is a newly-established building which serves as a fledgling museum and library.

The original Tolstoy Farm covered 1 100 acres, and already had nearly 1 000 fruit-bearing trees in May 1910. Water was supplied by two wells and a spring, and the soil was fertile. The settlers constructed three shed-like structures of wood and iron, none of which remain.

Mohandas K Gandhi (1869-1948) attributes the success of the final phase of the Satyagraha campaign in South Africa between 1908 and 1914 to the "spiritual purification and penance" afforded by Tolstoy Farm.

Gandhi founded two settlements for community living in South Africa where he developed his philosophy and techniques of non-violent change, called S atyagraha. The first was Phoenix near Durban in the Colony of Natal, founded in 1904, where the printing press for Indian Opinion, a newspaper he began, was based. Then followed Tolstoy Farm outside Johannesburg, which ran from May 1910 to January 1913, which was meant for training and preparing people for S atyagraha. Gandhi was not as personally involved in the daily running of the Phoenix settlement as he was to become at Tolstoy Farm.

Tolstoy Farm has been described as a “cooperative commonwealth”, a term coined by Gandhi. It had a distinct pattern of life which was to be upheld by each member and was practised with the hope that it would spread to others. Virtues extolled on the farm revolved around simple living, manual labour, and respect for diversity.

Before delving into the daily activities of the farm we must note the context and pressures under which Tolstoy Farm was formed. Starting in 1893, Gandhi journeyed to South Africa as a young lawyer. After becoming aware of the social injustices at the time against the Indian community he formed and later honed his philosophy of non-violent resistance which he called ‘Satyagraha’. He went on to become a leading voice for Indian rights, first in Natal and then in the Transvaal. The activism played out as protest action, negotiations with the government, mobilization of the community and deliberate mass imprisonments to persuade the government to abolish oppressive laws against the Indian community.

The idea to establish Tolstoy Farm came after Gandhi was imprisoned for three months in 1909 during which he read thirty books, one of which impressed him greatly: The Kingdom of God is within you by Leo Tolstoy the Russian author. This stimulated his search for truth and non-violence within his own religion, and prompted him to reach out to Tolstoy in four letters where he narrated the struggle of the Transvaal Indians.

Together with his architect friend Hermann Kallenbach, Gandhi developed the idea to formulate the idea of acquiring a farm that would meet the needs of the Indian resistance movement, by providing work for all, and bringing in money as well as an opportunity to experiment with new modes of communal living.

Since the centre for his campaign was in Johannesburg, the farm would have to be close to Johannesburg. This is where architect Herman Kallenbach stepped in, an ardent follower of Gandhi. As Indians were not permitted to own land, Kallenbach purchased a farm and placed it at the disposal of the Satyagrahis in 1910, rent free, for as long as the campaign lasted.

A shed and dilapidated house with four rooms was used as shelter but the open space allowed for a simple life away from the distractions of the city. The people who settled there stayed in tents while a 50-foot long dormitory for women was built first, then later a larger one for boys and men while the third building was used for offices, a workshop and a school.

The farm was called Tolstoy Farm at the suggestion of Kallenbach, as the experiences that Tolstoy described in Tolstoy’s book My Confession resonated deeply with Kallenbach and he felt spurred on to follow Tolstoy’s ideals.

The community was headed by Gandhi, and included Kallenbach and a few other white supporters. Indian families were of different backgrounds and faiths - Moslems, Christians, Hindus and Parsees – and spoke different languages, such as Gujarati, Hindi and Tamil and English. They stayed for short and longer periods, and in total there was a fluid population of 70 to 80 residents at any time.

Since the establishment of Phoenix, Gandhi had become acquainted with the Tolstoyan movement which spawned co-operative colonies in England and elsewhere. He recognised that his community was not isolated but part of a worldwide social justice movement.

JD Hunt (1998) writes that Gandhi tried to learn from shortcomings at the Phoenix settlement, and Gandhi explains in a letter to his cousin Manganlal how he would envision life on the new farm: “There would be no private garden plots; all would cultivate the entire land together. There would be one kitchen and common meals. There would be neither private homes nor family living quarters. The Farm would not be a village of families but one joint family”, in which Gandhi acknowledged he would play the role of the father.

Tolstoyan ideas on the importance of hard labour were palatable, as physical labour was strongly emphasized, firstly in construction of the buildings, then the fields and the orchards. Furthermore, the training of the satyagrahis encompassed recreating a prison-like experience in order to ready them for the harsh conditions of imprisonment when arrested for passive resistance marches, the training was aimed to produce discipline and self-control. The men wore coarse blue workingmen’s trousers and shirts much like prison uniforms. Sandals were worn in consideration of the warm weather. Food was served in a single bowl such as prisoners use, and wooden spoons were the only utensils used. Residents wanting to go into Johannesburg ordinarily walked approximately 35 kms each way to and from the town. For medical care they used natural methods such as fasting, dietary changes, and treatments using earth and water.

A Rand Daily Mail reporter described the daily schedule on the farm. A bell rang at 6am in the morning, before eating breakfast the residents would relieve themselves then make their beds. At this point everyone was assigned a task for the day; at about 11am all work ceased. They would take baths on the warm day, then lunch would be served. At 1pm school began with several classes that lasted till 5pm, after which dinner was served at 5.30 pm. An hour of rest, then at 7pm residents would gather before Gandhi who reviewed the day’s events, by addressing challenges and seeking solutions. The meeting would end with readings from books on religion and singing of hymns.

The school at Tolstoy Farm was described in 1912:

“Manual training is combined with mental but the greatest stress is laid on character-building. No corporal punishment is inflicted, but every endeavour is made to draw out the best that is in the boys by an appeal to their hearts and their reason. They are allowed to take the greatest freedom with their teachers. Indeed, the establishment is not a school but a family, of which all the pupils are persuaded, by example and by precept, to consider themselves a part. For three hours in the morning the boys perform some kind of manual labour, preferably agricultural of the simplest type. They do their own washing, and are taught to be perfectly self-reliant in everything. There is, too, attached to the school a sandal-making class, as also a sewing class…No paid servants are kept on the farm in connection with either the school or the kitchen. Mrs Gandhi and Mrs Sodha, assisted by two or three pupils, who are changed every week, attend to the whole of the cooking. Non-smoking, non-drinking and vegetarianism are obligatory on the farm.”

An effort was made to teach the students that they are first Indians before anything else, and that they should remain true to their own faith while respecting others’ beliefs. Unfortunately, the school that had grown from 5 students to 25 in two years, was short lived.

Tolstoy farm closed quite abruptly after little more than two years. Following the visit of Indian statesman G K Gokhale, which led him to believe that a final settlement with the Union government was at hand, Gandhi decided to leave Tolstoy Farm in six months’ time. By January 1913, Gandhi and the school left the Farm for Phoenix.

Upon returning to Phoenix, Gandhi introduced some of the practices instituted at Tolstoy Farm such as the common kitchen, physical labour and communal ways of living with his chief focus being the school. Passive resistance resumed in September 1913 in which Gandhi led his 16 residents from Phoenix, both male and female, on foot through the Transvaal, aiming to go to Tolstoy Farm. As news spread he ended up with an army of strikers and over 20 000 Indian workers on strike all over Natal. Thisled to the passing of the Indian Relief Act.

The Indian Relief Act marked the end of the Satyagraha campaign, which extended from 1906 to 1914. After that, Gandhi felt free to leave South Africa, taking with him members of his ashram community and intent on bringing Satyagraha to India.

In June 1915, he established a new ashram at Ahmedabad in India, following the model of Tolstoy farm. The constitution for the Satyagraha Ashram in Ahmedabad was the direct fruit of Gandhi’s South African experiments, based on the idea that ethical action must be effectively organized through “a centre of spiritual purification and penance”.

After initially renting out the farm in 1913, Kallenbach sold the property to W H Humphries under Deed of Transfer 14040/34, and Humphries later transferred the property to the Anglovaal Brick and Tile Company.

Efforts to revive public interest in the site began in the late 1960s when the Transvaal Centenary Council (TGCC), established to mark the Centenary of Gandhi’s birth (1969), conceived the idea of preserving Tolstoy Farm as a Monument.

The following account of the project is given in Gandhi’s Johannesburg: Birthplace of Satyagraha:

“After negotiations the Company donated a small portion of the farm – a brick house and four acres of surrounding land to the TGCC in 1974. The house which was very run down, was assumed to be Kallenbach’s original dwelling. There was no sign of other buildings on the site.

The house was restored by the Centenary Council in about 1982, but by 1996 the building had been almost completely destroyed by vandals, leaving only stumps of walls. After consultation and soul-searching, the TGCC resolved to restore the house up to plinth level and to cement the floor. This is the way it has remained – only the floor space of the original house can be seen.”

By 2014, Corobrik, a South African Brick Company, who are the current owners, agreed to hand over this portion of approximately four acres to the Mahatma Gandhi Remembrance Organisation, to resuscitate the site and commemorate its Gandhian legacy.

This organisation built a new structure alongside the original house floor space, where it celebrates Gandhi’s key dates, including peace walks. School children visit the farm, and prayers are held across all religious groups, as well as picnics on the site. Hampers and blankets are delivered to local informal settlements.

The plinth structure has General Protection: Section 34 (1) Structures under the National Heritage Resources Act, 1999.

A culmination of research gathered over many years, the Online Johannesburg Heritage Register is being launched on Nelson Mandela Day 18 July 2025.

Among the many heritage sites featured is Chancellor House, the downtown offices of Mandela and Tambo Attorneys in the 1950s. After having been vacant and shuttered for more than a decade, this iconic building is being revived and brought to life once again as offices for the Community Development Department, which oversees the City’s Arts, Culture & Heritage Services.